Future Reflections on Creativity

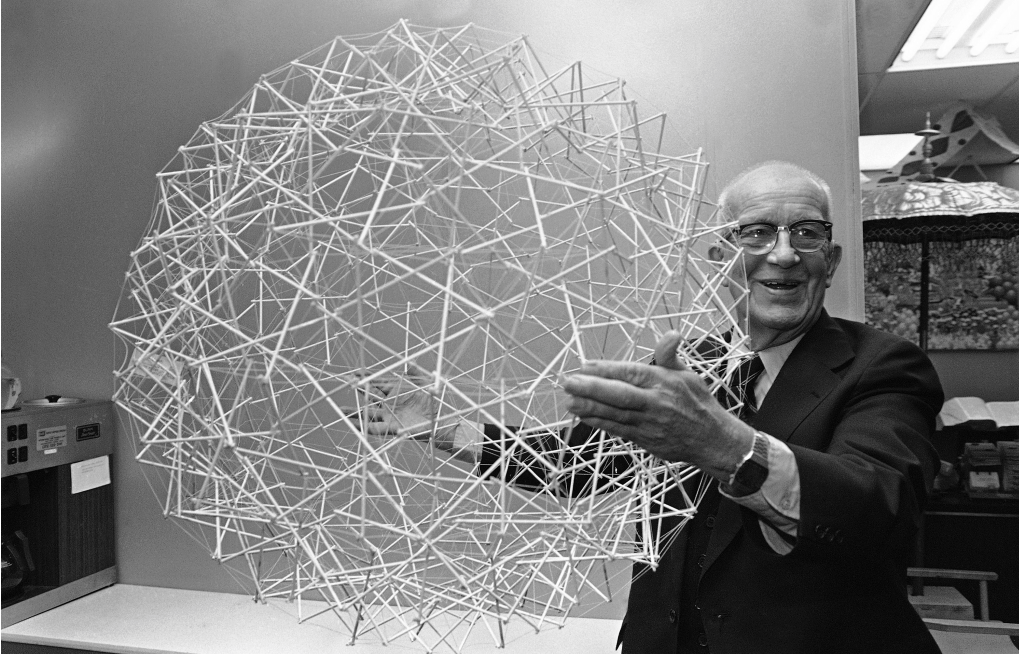

Buckminster Fuller

It is always a challenge to talk about culture and to offer something new on a subject that is as old as civilization itself. This latter point came to mind when I was viewing Werner Herzog’s new film Cave of Forgotten Dreams which is shot in 3D and takes place in the Chauvet Caves in France. The images in the cave are at least 30,000 years old. The Chauvet Cave images reflect an extraordinary desire to picture the world since they were created under very difficult circumstances, most likely with very little available light but by artists with exceptional talent. The images reflect a deep desire to connect aesthetics with form. They are all closely linked to each other, inadvertently creating a narrative that may well have been repeated in many other caves and in many other more distant locations. This suggests that not only is the creation of art fundamental to the human psyche, but also that humans could not survive without it.

As Brian Boyd recently suggested: “A work of art acts like a playground for the mind, a swing or a slide or a merry-go-round of visual or aural or social pattern.” (15)

The integration of play with creativity and curiosity seems transparently clear to those of us who have devoted our lives to the arts, but for reasons that I will discuss in this post, as much as we recognize the importance of art, we also devalue its role, contribution and voice. The 21st Century could be one of the great golden ages for the arts. My hope is that it will be. But, there are storm clouds on the horizon that we all need to be watchful about.

Over the last fifteen years, the cultural sector along with the small number of institutions devoted to learning in and for the arts in Canada have been involved in a difficult and challenging debate.

On the one side, some argue that culture is essential to the fabric and nature of Canadian society and that culture defines not only who we are, but also how we live and in some instances how we should live. On the other side, are advocates for what I will describe as the economic argument for the arts using the term Cultural Industries as a catch all for culture’s contribution to the GDP and to the economic well being of our society.

I believe both positions need revision and rethinking because we have reached a crucial phase in the broad based discussions that our communities are having about culture and its importance.

First, we need to understand that there are many definitions of culture, so many in fact that the term itself has lost some of its power. This is not a minor issue because in its present usage culture encapsulates nearly everything we do, which means that we have no clear definition for it and no way of distilling what is special about creative engagement and the creative life. This has implications for the role and importance of artistic engagement, because we end up replacing the uniqueness of creativity with assembly line notions of production and consumption.

Second, it is proving to be very difficult to sustain the argument that creative cultures are essential to our everyday lives. As our economic crisis deepens, various cultural activities appear superfluous even as people seek out alternative venues to relax, learn and be entertained. Although not a given and very dependent on context, creative work is also meant to challenge, sometimes caustically and more often with positive intent rather than a desire for negative outcomes. These sometimes contradictory tendencies make arguments about the value of culture more challenging but no less important.

What we are seeing today are divisions among various creative forms with some like interactive gaming appropriating the history of aesthetic expression in media and fine arts for popular purposes while others in the visual arts continue to rely on an exclusive gallery system for validation. This separation has its own challenges, not the least of which is the decline of serious art criticism in our newspapers and the almost complete absence of art journalism among mainstream broadcasters who might explore these divisions and articulate and critique their value.

At the same time even as these contradictions come into play, we are undergoing a massive conversion to digital technologies and it FEELS as if artists are leading the way. I say feels because if you take a close look at what is happening you will notice that cultural creators are still for the most part ensconced in the same fragile relationships that they have always had with the state, the business community and the population at large. Despite all of the discussion of DIY cultures and social media and despite the societal recognition that creativity is at the heart of what we do, the gap between artists and their communities has not changed all that much in the last fifty years.

Digital cultures are hugely democratizing because they encourage many different forms of creative output, but this does not mean that the works being produced will find a significant place in our society or be recognized as important from an historical point of view. In fact, we now need more and more sophisticated curatorial strategies to even understand the range of what is being produced. So much is being created that we are inverting and dissolving conventional notions of high and low culture and this is leading to what I will describe as a series of micro-cultures. Micro cultures are both an exciting development and also full of pitfalls. They reflect the increasing fragmentation of cultural activity into interest groups often driven by very narrow concerns. At the same time, they represent a profound change in the conditions which drive the production of creative work and the distribution of creative output.

Why does the creation of cultural artifacts so essential to our sense of community and nation exist in such a fragile relationship with the population and government? If there is a consensus that the arts are important, why do most cultural organizations struggle and in many instances rely on government funding and public philanthropy for their survival? The only conclusion that can be drawn from these contradictions is that cultural creativity is not that essential, which is why cultural organizations are always the first to feel the sting of government cutbacks. I will return to this point in a moment.

The continued pressure to identify the arts in particular as functional parts of a cultural economy carries with it many dangers. One of the most serious is that we conflate the deeply felt desire on the part of a significant number of people in our communities to satisfy their yearning to create, with the outcomes of that creativity. It is so important to understand that creativity does not necessarily mean that there will be identifiable and valuable outcomes to the process. The key word here is process. It is the same with learning. If all we are aiming for are outcomes, then we will end up with a linear process, one that is predetermined by what we anticipate from it. Part of the joy of creativity and learning how to be creative particularly in the arts is that we don’t know exactly where we will end up nor do we often know why we even began.

The joy here comes from the quest. And if the final object, process or event reflects our deepest sense of what we want to say and why, then that should be enough. As we know, in the present context, it is not.

We need to sharpen our understanding of this contradiction. In the 18th century culture meant something very specific, usually related to crafts and to guilds. Although many of the arts were practiced in elite contexts and produced for the elite, the distinctions between creativity and everyday life were neither sharp nor seen as necessary. In other words, the boundaries between the arts and other activities were permeable.

Over the last fifty years or so that permeability has decreased to the point where creative practices are now classified as one of many professions. In fact, from a policy perspective, the systems of classification that we have in place are very convenient. However, and quite ironically, if creators are engaged with their work, they are likely to make a mockery of the classifications largely because the voyage of creative engagement often has no clear purpose and may try to obscure or critique its use of genre or tradition. This is in fact the opposite of what traditional professions are designed to accomplish, which is why the most current word used to explain how people enter various professions is training. Purpose of course has many meanings as well as outcomes. The same issue haunts research. If it is too directed towards outcomes then there will be few surprises and innovation will be stifled.

So, to repeat, we need to understand that the creative act is never singular in character or in action, never clearly purposive although filled with intention. Creativity is very much about crossing and challenging boundaries not only between different disciplines but also among different practices. Creativity has economic power and impact, but that is not its only role. Creativity produces cultural artifacts but that is only part of the importance of culture to everyday life.

As the distinctions between many professions and artists has grown wider and wider, and as the boundaries have become less permeable, it has become difficult for discussions to take place among the different and sometimes contesting sectors. There may well be many similarities in process and outcome among these sectors, but the walls between them have become more solid and not less as many assume.

The best example of this is the profound disempowerment of artists from the activities of programming for digital tools. A very small minority crosses this increasingly solid boundary, but for the most part artists have to use tools developed by computer scientists working from assumptions that are steeped in a misunderstanding of creativity and most importantly, the history of art.

Although David Hockney does some amazing things with his iPad and iPhone, he has no control over the programming language that is making it possible for him to work in the medium or with the technology. He has overcome some of those limitations but must recognize that he cannot push too far without having to learn much more.

My point here is that boundaries are important and although different disciplines have different histories and practices, one of the most important learning experiences for artists is their ability to break the mold, and to challenge conventions and expectations. When creative engagements are classified according to crafts or techniques and when artists are classified according to their ability to practice those crafts, the purposes and potential effects of artistic engagement will be diluted. To know and really understand programming means far more than gaining a handle on using code. It means integrating the conceptual requirements and impact of coding on creativity and engagement with materials of all sorts. But, that also means that materials will change, forms of interaction with audiences will be transformed and most importantly, artistic practices and disciplines will shift.

Nomenclature is important but it also must be open to challenge. Training for example, is quite appropriate for certain professions because their activities are circumscribed, defined and quite concrete. We definitely want to train the pilots who fly our airplanes and the construction workers who build what our architects design. Some aspects of the cultural production pipeline need people who are well trained. But, writ large, individuals cannot be trained to be great artists. It is just more complex than that, much more complex. Learning how to use different media and different forms of artistic expression involves more than learning the tools or even the craft. The entire process requires profound self-examination, critique, self-analysis, public comment and more. Somehow, training as a term does not capture the complexities of all these activities.

So, let me return to an earlier point about whether creative engagement is an essential part of our society. As I said, arts organizations are always the first to be cut back as I might add are educational institutions. Have we missed something?

I speak to many different audiences from all walks of life. What always amazes me is the nostalgic warmth people feel for the arts. Many talk wistfully about wanting to be artists, others remember specific moments when they were moved by a poem or a painting or an opera. The extraordinary proliferation and use of digital cameras/phones can be traced to this nostalgia, this desire to find some means, any means to express our perceptions, to summarize our experiences, to perhaps shed new light on the ordinary activities of looking, walking or talking.

Yet these same people will rarely lift a finger when the arts are removed from high schools or local cinemas fail. And, make no mistake about it, policymakers know this and in some senses exploit what seems like a very obvious conundrum. My own sense is that the arts are both attractive and repulsive, the former because of this strong desire to be expressive in many different ways, the latter because creative release, creative realization threatens not only convention but also existing patterns of daily life.

Often, art disrupts and in the process lays bare some of the contradictions of our daily lives that we are sometimes not prepared to explore. This disruptive effect, so inherent to the learning and creative process, so crucial to growing and changing can also be profoundly disturbing. There is then a deep ambivalence about creativity and about our imaginations, about the dreams and nightmares of putting oneself on the line and about the risks inherent in exploring new ways of seeing oneself and the world.

The work of being an artist or a designer or a media creator is centred on rigour and on being able to sacrifice the time and energy to understand one’s intentions with as much depth as possible. This requires time, a real commitment of time, going beyond the boundaries made possible by a consumer oriented society and stepping with great trepidation into the unknown, a landscape without maps.

Here is a quote from Steven J. Tepper and George D. Kuh in a recent article in the Chronicle of Higher Education:

“A recent national study conducted by the Curb Center at Vanderbilt University, with Teagle Foundation support, found that arts majors integrate and use core creative abilities more often and more consistently than do students in almost all other fields of study. For example, 53 percent of arts majors say that ambiguity is a routine part of their coursework, as assignments can be taken in multiple directions. Only 9 percent of biology majors say that, 13 percent of economics and business majors, 10 percent of engineering majors, and 7 percent of physical-science majors. Four-fifths of artists say that expressing creativity is typically required in their courses, compared with only 3 percent of biology majors, 16 percent of economics and business majors, 13 percent of engineers, and 10 percent of physical-science majors. And arts majors show comparative advantages over other majors on additional creativity skills—reporting that they are much more likely to have to make connections across different courses and reading; more likely to deploy their curiosity and imagination; more likely to say their coursework provides multiple ways of looking at a problem; and more likely to say that courses require risk taking.”

More and more, curiosity, imagination, taking risks are being valued by industry and by communities.

Let me briefly comment on the argument around the creative industries because the term carries so much power and is in my opinion fraught with difficulties. While it is true that 8% of the Canadian GDP is creative, this is based on a very broad definition of the cultural sector. Even though the GDP of the creative industries are in total greater than mining and forestry combined, the creative industries as a label both takes in too much and describes too little. The difficulty is that industry suggests assembly, manufacturing, production and trade. Its original 15th century meaning was more related to diligence, cleverness and skill.

“The current definition of the creative industries is based on an industrial classification that proceeds in terms of the creative nature of inputs and the intellectual property nature of outputs.” Jason Potts, Stuart Cunningham, John Hartley and Paul Ormerod, Social network markets: a new definition of the creative industries Journal of Cultural Economics Volume 32, Number 3 / September, 2008, 167-185.

You can begin to anticipate where I am going with this. It is not that markets and commerce are in any way in contradiction with creative work, it is that the label, the nomenclature makes it seem as if creative work can be framed and packaged. This is the dilemma. Entrepreneurship is at the heart of most creative work, and yet that is neither the sum of what artists do nor the metaphor that best describes their work.

Think of it this way. Ambiguity is at the heart of working on and developing an art work. There is no direct line from an idea to a product or a painting or a film. In fact, ideas themselves travel indirect routes from their progenitors to viewers or consumers. This is a complex system and not a simple one. There has never been a complete map of creativity because in large measure so much of the process is driven by multiple strategies, some intuitive and others more specific, more empirical. The beauty of creativity is precisely that we cannot contain its excesses, cannot simply frame its meanings, cannot reduce what we do not know or understand to simple formulae.